Most of the world’s glaciers have been in retreat since the late 19th century as the climate has warmed. Balog felt that single-frame photography could not capture changes in the cryosphere through time. By December 2006, he settled on the idea of deploying a network of time-lapse cameras to document the action.

The Extreme Ice Survey played a pivotal role in shifting public perception of the immediacy and reality of climate change. The project became the subject of the 2012 documentary film, Chasing Ice (winning an Emmy award and the Sundance Film Festival award for cinematography, as well as earning a shortlist nomination for the Academy Awards and many other accolades from around the world); the 2009 PBS/NOVA special Extreme Ice; the 2024 documentary Chasing Time; three feature stories in National Geographic magazine (2007, 2010, and 2013); and dozens of stories on television (ABC, BBC, CBS, CNN, NBC), radio, internet, and in print media.

James founded and led EIS. Many American scientists, particularly Jason Box and W.T. Pfeffer (then on the faculties of Ohio State University and University of Colorado, respectively), were important allies in the development and funding of the project. Other key advisers and allies from academia included Alberto Behar, Dan Fagre, Eran Hood, Konrad Steffen, and James White.

Inventing, engineering, and constructing a system of custom-made time-lapse cameras durable enough to endure the rigors of polar and alpine winters was a substantial challenge. Powered by photovoltaic panels, the camera systems made photographs during every hour of daylight (later, the time interval shifted to every half hour) throughout the year. The cameras continued to function through torrential downpours, fierce blizzards, and temperatures as low as -40 degrees Fahrenheit (-40 degrees Celsius).

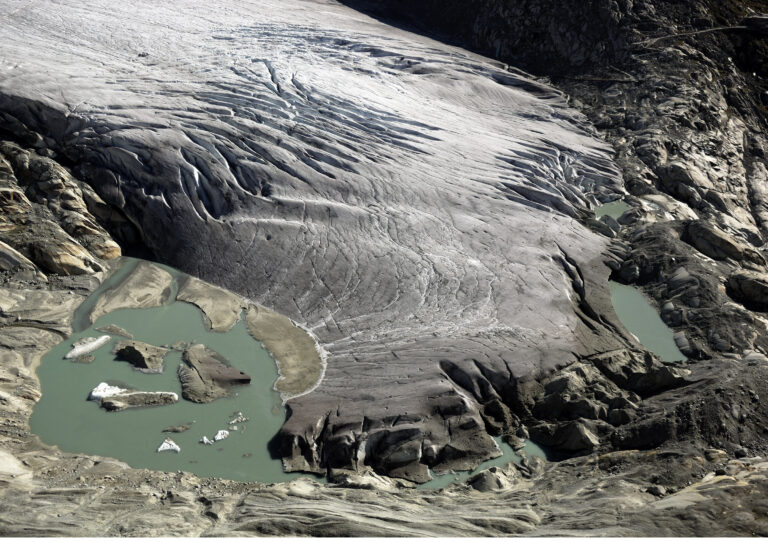

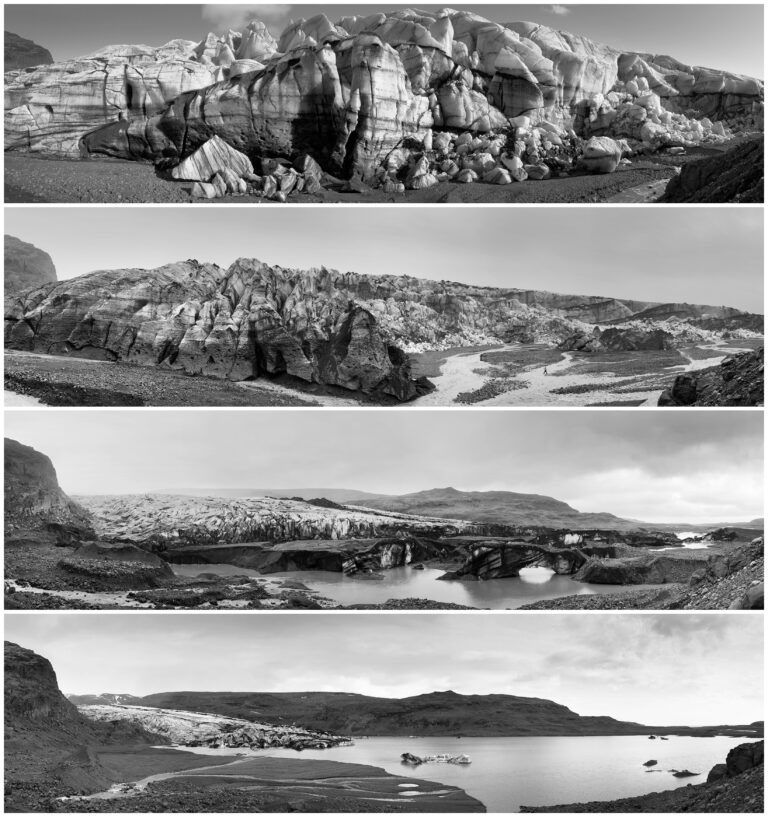

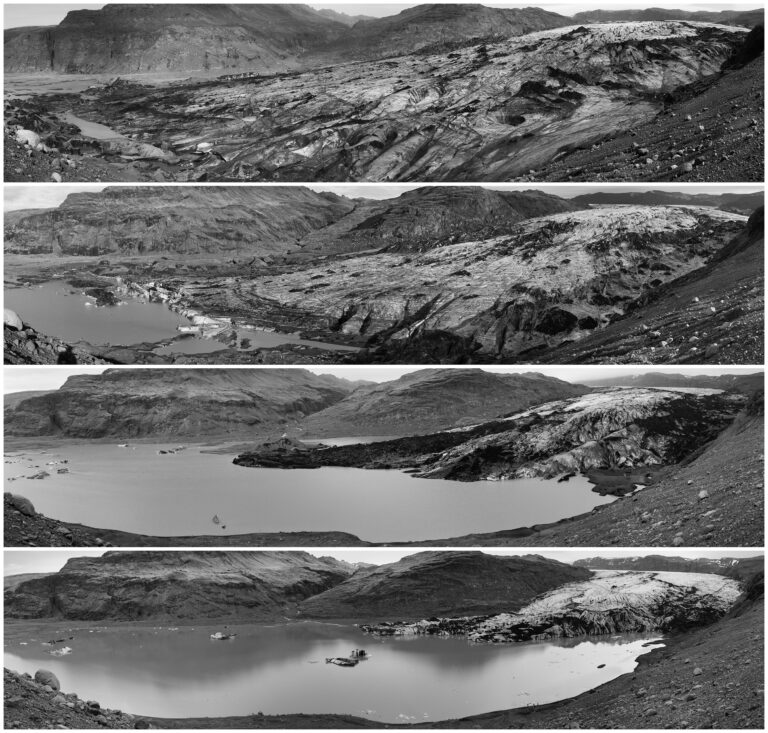

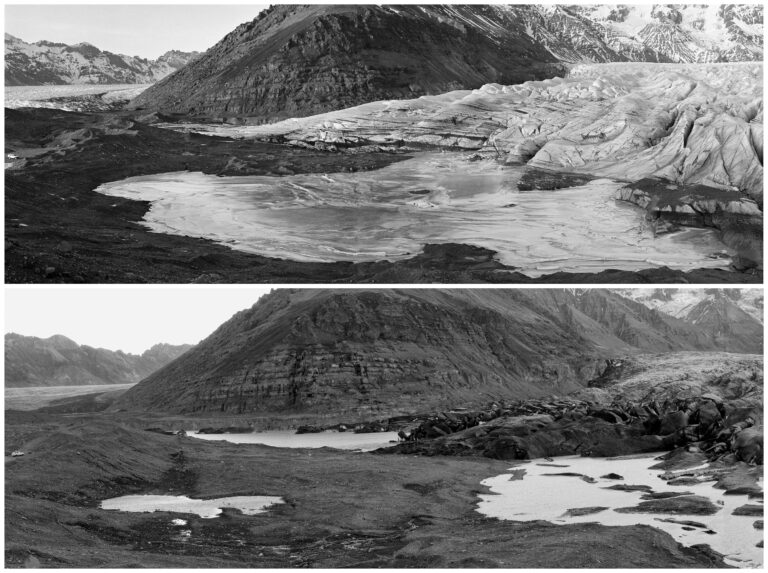

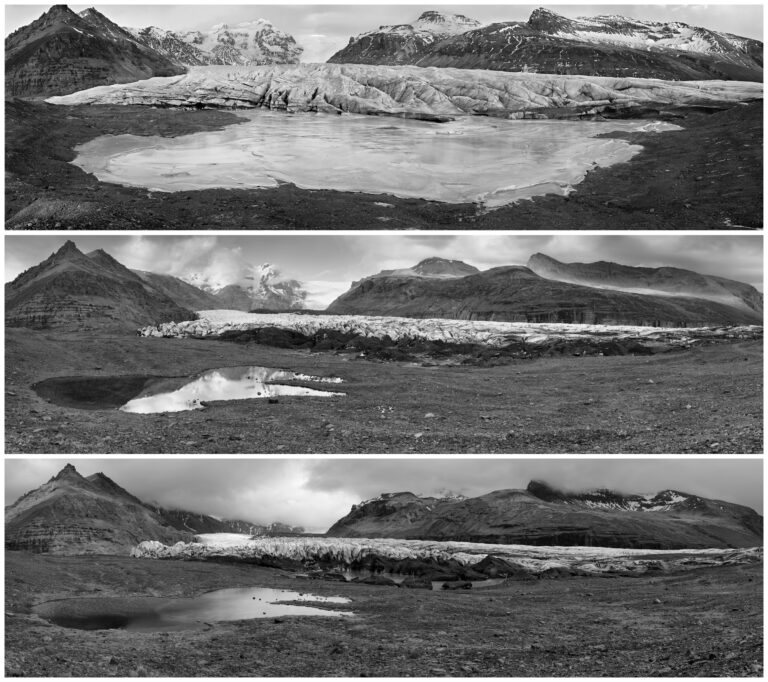

Between March and July 2007, the EIS team mounted an initial deployment of 24 camera systems on rock walls above and alongside glaciers in Alaska, Greenland, Iceland, and northern Montana. Eventually, a total of 72 time-lapse cameras were deployed in those locations, as well as at Mount Everest in Nepal, and in Antarctica, South Georgia, and Austria. EIS team members would revisit the cameras at intervals from a few months to a few years to download images. Other photographs were generated by repeating images at fixed locations year after year.

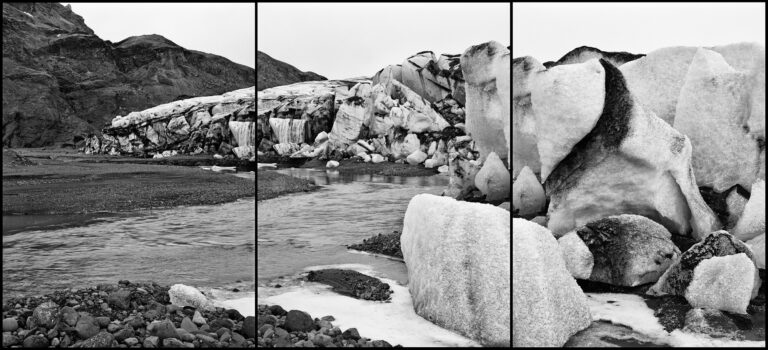

The images presented here were selected from the 1.5 million frames of EIS digital time-lapse imagery in the permanent archives of the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado—showing, in intricate detail, the deep connection between ice, weather, climate, and time.

"There is no such thing as glacial pace. Ice responds by the minute and hour to the touch of air and water around it,” James writes in Ice: Portraits of Vanishing Glaciers (2012). “In ice is the memory of our world. Of sunlight and darkness. Of molecules hot and cold. Of our spinning planet plunging through galactic space. Ice sees and hears and feels the pulse of a changing world. Layers of ice remember all the heat and cold, all the snow and rain, the fallout of smokestacks and tailpipes, of wildfires and nuclear bombs. On secret diamond faces, nature encodes stories of time past and foretells the future. Tales trapped in ice reveal where we’ve been and where we’re going. Monumental change is not something happening in the dim past or vague future. Monumental change is happening right now, in different ways, in different places, east and west, north and south, overhead and under our feet."